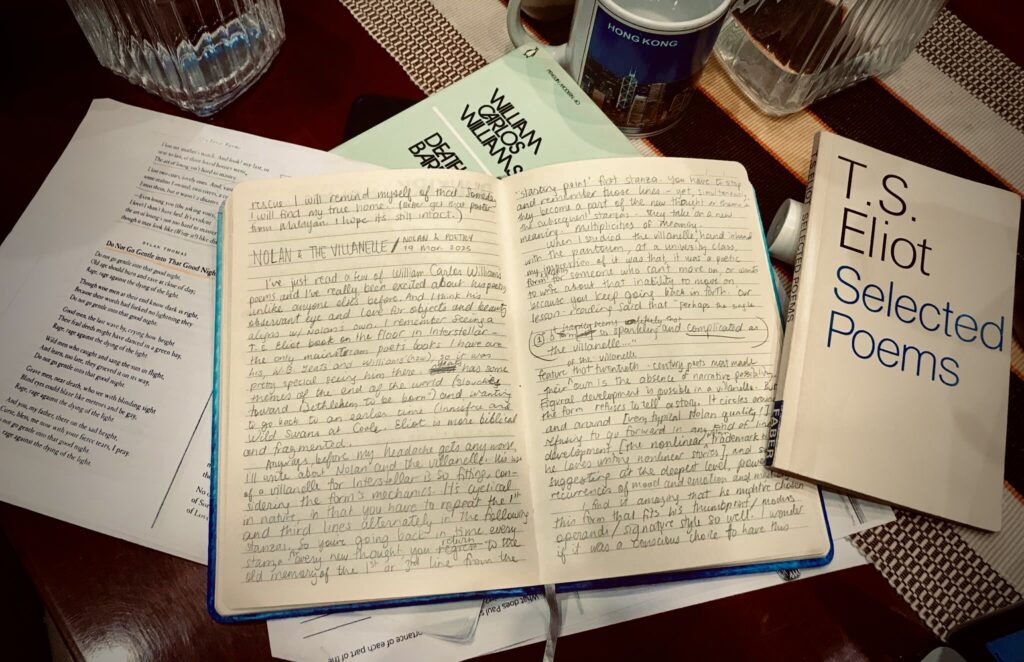

Christopher Nolan and the villanelle – what a combination. (For the readers who haven’t heard of the villanelle before, it is the poetic form of the poem that appears in Interstellar. I’ll explain it in length in this post.) Some months ago, I was pondering about Interstellar’s themes and I remembered how, from my very first watch years ago, I appreciated the use of poetry in the film. Listening to, studying, and writing poetry is one of my hobbies, and I also recently revisited the homework handouts I’d printed while I took a Creative Writing: Poetry class at university some years ago. The villanelle was one of my favourite forms to work with back then, and, of course, one of the poems that appeared in the examples of the handout on villanelles was the poem that appears in Interstellar (it is probably the most popular villanelle).

Since I was in my Christopher Nolan phase at the time (I still am lol), I realised how the mechanics of the villanelle suited not only the film, but Nolan’s style itself. Here is my exploration of those ideas (which took me a few months to finally write down here – a day after World Poetry Day!)

(Warning: Interstellar spoilers ahead.)

So, one of Interstellar’s motifs is the use of some lines from Welsh poet Dylan Thomas’ “Do not go gentle into that good night”…

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

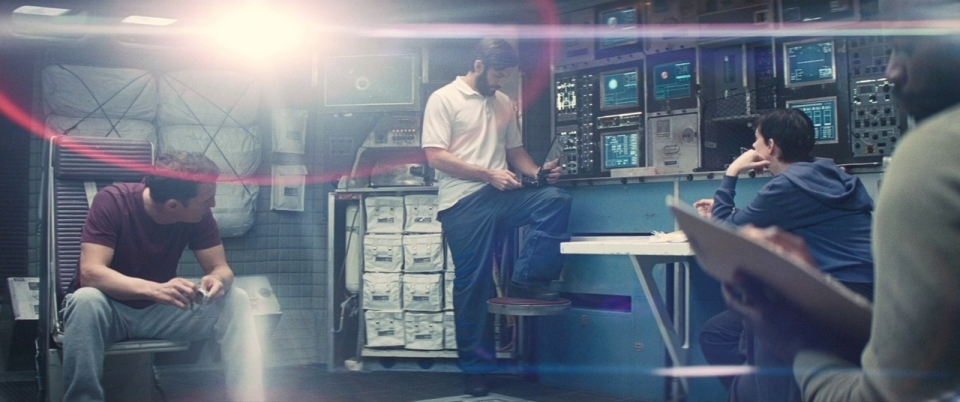

The elderly Dr. Brand reads it out as Cooper’s crew lifts off and heads toward a different galaxy to save the Earth. It recurs in other parts of the film, like when Dr. Mann is killing Cooper, and it appears on a monument for all the astronauts involved in the effort to save Earth. It’s a fitting poem for the film’s theme of fighting death and the dying of the Earth’s light.

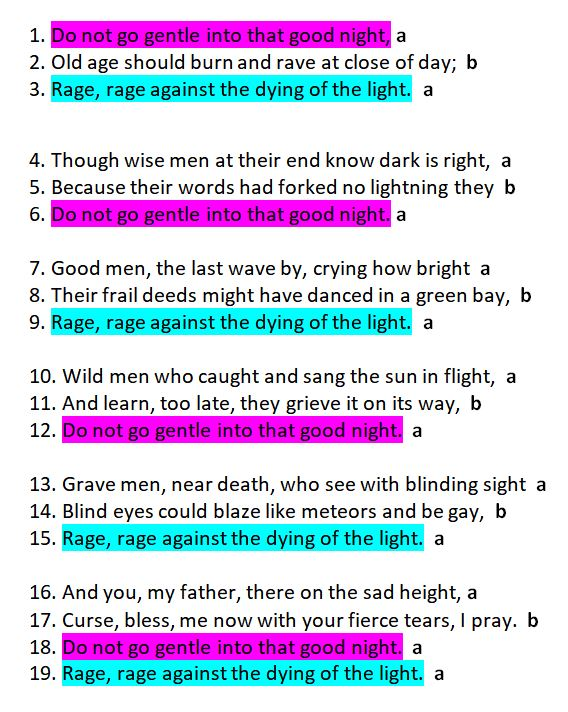

But I found something deeper looking at the form of the poem itself. “Do not go gentle” is a villanelle, a strict poetic form characterised by refrains that are repeated throughout the poem – kind of like in a song. For example:

Studying this in poetry class at university (my prof was also British like Nolan 😆) and being required to write a villanelle poem myself, I found that it’s hard to tell a straight story with it – but, it’s rewarding to make it work. My prof also said with a smile, “You have to find good first and third lines – it’s better if they sound catchy, hah, because you’ll have to repeat them all over the poem.”

And, like Thomas, I wrote a villanelle about grief (it used to be on this blog before all my posts were erased). I’ll come back to this theme of grief and loss later so I can talk more about the poetic structure of the villanelle.

But yeah, when I first studied the villanelle, my impression of it was that it was a poetic form specifically for someone who can’t move on – or wants to write about that inability to move on – because in a villanelle, you keep going back and forth. I later connected this to Interstellar.

Parallels between the villanelle, Interstellar, and Nolan’s filmmaking style

So, considering the poetic form’s mechanics, I realised that Nolan’s use of a villanelle for Interstellar is so fitting. It’s cyclical in nature, as you saw in how Thomas had to repeat the first and third lines alternately in the stanzas that make up the body of his poem. (And the circular motion/motif reminds me of the visual motif of the Endurance, which is a circle! Also, as you may have read before, it looks like a clock 😉.) So, you could say you’re going back in time every stanza – to recap: for every new thought, you return to the old memory of the first or third line from the “starting point” first stanza. You have to stop and remember those lines – yet simultaneously, these lines become part of the new thought or theme in the subsequent stanzas they belong to; they take on a new meaning. Multiplicities of meaning.

The idea of going back in time is related to Interstellar’s plot – as Cooper discovers in the black hole-tesseract scene that he can use gravity to affect the past, and somehow go back in time, if only to see his daughter from beyond a “bookshelf”. He’s kind of in a loop in that tesseract dimension, replaying scenes from his past with his young daughter. He can’t move on – until he finishes his purpose to save the humanity that’s left on Earth.

I also find it amazing that Nolan might’ve chosen this form that fits his modus operandi or signature style as a filmmaker so well. I wonder if it was a conscious choice to pick a villanelle, or he just liked the poem and later found out how the form fits his style. As an English Lit student, I’m sure he put some thought into it – I’m betting they studied the structure at University College London where he studied. I wonder if he liked the villanelle form itself and was drawn to it like I was – perhaps the complication of it appealed to him.

A little tangent here: I already found a magnetic pull to his penchant for nonlinear narratives because of my history as a third culture kid; the confusion of those narratives is somehow comforting because I’m used to moving around the world, and sometimes feeling like I’m stepping out of a time machine when I go back to my home country. I’ve also written before how I view Nolan as a quasi-third culture kid with his upbringing in both the UK and the US, and my interpretation is that he thrives on complication and complex challenges because it can be challenging (sometimes) to deal with different cultures, even if it’s your own (hello, reverse culture shock). I guess I was influenced by seeing how his brother, Jonathan (who co-wrote Interstellar), has an American accent while Christopher has a British one – I mean, that’s crazy and super cool 😆 but it just shows how you can choose to adjust to different cultures… anyways. Now I find it special that he also picked a poem in one of my favourite forms as a significant marker in his film. Okay, tangent over.

Making a villanelle is difficult and complicated compared to other forms, in my opinion, because you have to think of how to string your ideas together and plan them out while writing. Firstly, as mentioned before, your first and third lines basically have to sound good 😂 and have some recall, because they’re going to appear four times in the poem. Secondly, your semblance of a narrative, or collection of themes per stanza, have to connect to either the first or third line – there has to be some logic. As a whole, the logic you put in the themes of the stanza and the organisation has to work.

On top of that, if you want to strictly follow the form, you have to think of an aba rhyme scheme! (And if you’re goated like Dylan Thomas, you’d work with a strict meter like an iambic pentameter. BRUH. this guy’s a genius… I could never.) Plus, if your last word’s potential for rhyming in the first/third line is limited, you have to think twice about using it, because you have to find other words in the next stanzas that work with it AND with the themes you’ll be writing about. (I learned this the hard way.) The final quatrain (i.e. stanza with four lines), therefore, is probably the easiest part – ending the poem is easier than planning out the whole villanelle above it.

If you’re not confused now, well. 😂 At least now you know writing a villanelle is a messy business 😅 And I’ll wager its complexity appealed a lot to Nolan.

The process of planning out a villanelle also reminds me of Nolan’s writing process, which involves making diagrams to plan out the ideas of his story – before he sits down to write the script (he refers to this in an interview about “Tenet”). I mean, how do you plan something like “Following” or “Memento”? How do you plan something like “Tenet” or “Dunkirk”? The dude is a genius. Well, at least he said it took him years to write those scripts, developing them in his head, and so on. XD

Maybe I should also make diagrams while writing villanelles. 😂

But yeah, coming back to what I said about how difficult it is to write a villanelle: It’s quite cerebral — accessing rhymes, thoughts to put in lines, how those new thoughts fit in together with the old, foundation or anchor lines, etc — but all the while you have to express an emotion powerfully for it to work. I think that’s also what Nolan is good at – the two sides of cerebral and emotional – he crafts and plans things very carefully and technically, all because he cares about how to provide a visceral, immersive emotional experience for the viewer. “Emotional mathematician” – Guillermo del Toro’s moniker for Nolan – comes to mind.

Nolan is also someone who likes to take on complicated things and solve them. I encountered an academic article that calls his movies “puzzle films” – Inception’s Singular Lack of Unity Among Christopher Nolan’s Puzzle Films by Andrew Kania in “The Cinema of Christopher Nolan” – which you can access here on ResearchGate. The villanelle is also one of the traditional poetic forms that represents how a puzzle is like, when you’re writing it (as for the written form, it depends. Sometimes they’re easy to understand.)

I remember those people who don’t like Tenet and Inception because they say that those films focus more on the concept and technical aspects, or they simply get lost while watching (I personally had to rewind lots of times just to get what was happening, which was fine with me) – and they don’t think those films hit emotional chords enough.

Point taken, and it reminds me of a phrase from the villanelle chapter in our textbook, The Making of a Poem by Mark Strand and Eavan Boland: “[t]he villanelle cannot really establish a conversational tone” because of its nature of going back and forth; not having a linear timeline, so to speak (just like Nolan’s films). Sometimes Nolan’s films are basically too difficult to understand and somewhat miss that “conversational tone” and clarity we expect from films (especially when the dialogue is so hard to hear!) I think some people miss the point of Nolan films because a) they’re unlike the narratives they’re used to (i.e. how events are mixed up in the timeline) and b) they’re hifalutin or overly technical sometimes. But I wish everyone would get the emotional heart of those films amidst all the nerdy stuff Nolan puts in them.

Another excerpt from Strand and Boland reminds me of Nolan’s style again (and somehow summarises the past paragraphs) – particularly the sentences I’ll put in bold: “Perhaps the single feature of the villanelle that twentieth-century poets most made their own is the narrative possibility. Figural development is possible in a villanelle. But the form refuses to tell a story. It circles around and around, refusing to go forward in any kind of linear development, and so suggesting at the deepest level, powerful recurrences of mood and emotion and memory.” Don’t his films do that, too?

Diving deep into Interstellar and the Dylan Thomas poem

Now that we’ve explored how the villanelle as a form is Nolan-esque (LOL), I’d like to share a few thoughts about how the Dylan Thomas villanelle and the form of the villanelle itself fit the “Interstellar” film. I’m sure other people have written analyses on this, drawing parallels from both works, but I’ll give my take on it.

Strand and Boland write, “And while the subject of most lyric poems is loss, the formal properties of the villanelle address the idea of loss directly.” In other words, the body of the villanelle symbolises loss. As we’ve explored its structure and mechanics, we see that it evokes the idea of not moving on – and Thomas’ poem is the quintessence of that theme: “rage, rage against the dying of the light”.

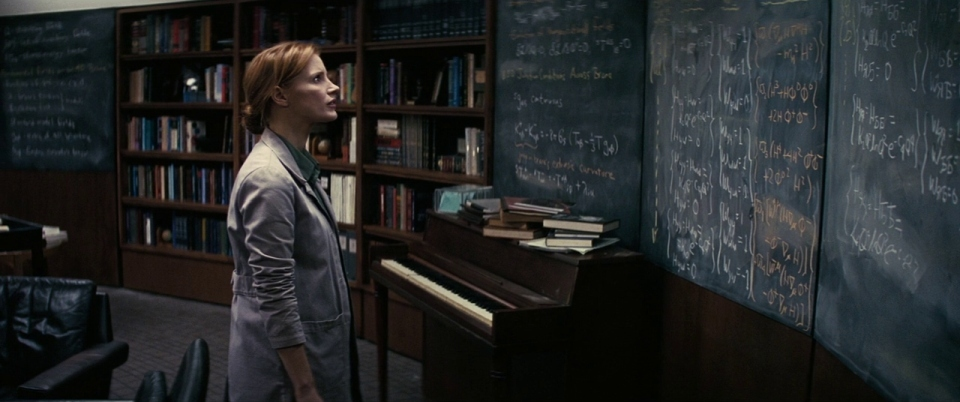

You could also say that the main, stirring themes of Interstellar are: the existence of loss, the impact of loss, and humanity’s refusal to cope with or accept loss. Cooper has lost his wife and he eventually loses his children; Brand loses her father, Edmunds, and the rest of the Endurance crew (she doesn’t know that Cooper is alive), and, before the events of the film, most of humanity died in some apocalyptic event. The main goal of the characters in the film is to escape death and/or shield their children from it. They want to continue humanity’s legacy, the “forked lightning,” the brilliance of human existence.

The poem talks about wise men, good men, wild men, and grave men. I’d say Cooper’s father-in-law Donald is the “wise man” of the story, giving Cooper advice about how to parent his children and wants him to make amends with Murph. Cooper is the “good man” who chooses the good for his children, but chafes at the thought that he never fulfilled his dream to fly in space, until the NASA people recruit him to save the earth. Dr. Mann is the “wild man” who “caught and sang the sun in flight” and learned, “too late,” that his planet was unliveable – and he is the negative example of someone who did not go gentle into that good night by 1. “raging” and tricking Cooper’s crew and many others with his false promise of a good planet, and 2. his death by explosion. I want to call the senior Dr. Brand the “grave man” because he is blind to the solution for gravity and was grave with the knowledge that there was no hope for the humans on earth.

And Murph is the one who cries “fierce tears” when her father, Cooper, leaves her. She looks up to the sky – “my father, there on the sad height”. This poem could be her own song to her father…

"Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light."

Well, I hope you enjoyed this analysis of both poetry and film. Let me know if it makes sense.

Have you read other villanelles before? Have you tried writing a villanelle? What movies do you like that have an element of poetry in them (don’t say Dead Poets’ Society 🤣 jk)? Does poetry deepen your experience of watching movies?